Editor’s note: This essay was first published in 2007 in Stylus, Todd Burns’ essential mid-aughts online publication. With recent news that rock ‘n roll magazine Creem is being relaunched — and last night’s onstage attack of Dave Chappelle at the Hollywood Bowl — Mr. Man suggested we repost it.

In the summer of 1974, while on an American tour and attempting a comeback, the Troggs were ambushed. Creem magazine, in its Rock 'n' Roll News section, reported that fighting broke out at the conclusion of a college gig, and that the band retreated to their dressing room. “The door was broken down and they were attacked by Hell’s Angels,” reads the news brief. “Among the injuries: guitarist Richard Moore was stabbed in the lung, Reg Presley suffered a broken nose, Ronnie Bond was stabbed in the neck, and Tony Murray was gashed by a broken bottle.”

Nothing more is mentioned of the incident—there’s no follow-up story—so the reader is left to ponder the many questions left in its wake:

What exactly did Reg Presley say on that stage? Whose girl did Ronnie Bond wink at? Did the Troggs have it coming to them?

A few months later in Creem, another entry in the “Rock 'n' Roll News” section reads: “Take Note Sly Stone … In Bangkok, a Thai folksinger, two hours late to a gig, was pelted with bottles by irate fans …But he, in turn, got so pissed off that he pulled a revolver and fired into the audience, wounding three.”

In January 1975, an item in the section reported that a California real estate developer was suing Elvis Presley for some $6 million, claiming he spent $60 for a ticket to a Lake Tahoe after-party thrown by the King. But Elvis’ aides “not only refused him entry, but started stomping his ass. The man claims further that he appealed to Elvis, who was watching the beating, to make them stop, and instead Presley joined in with a few well placed licks of his own.”

It’s hard work, being a rock and roller, almost as tough as being a fan. Shit happens. Feelings get hurt. Expectations collapse into disappointment. The whiskey, or the weed, or the amphetamines, goes to the head up on that stage, and then what? Somebody gets stabbed in the lung, somebody else takes a few bullets. The majority of the audience just gets pissed, complains until the next album comes out and then reassesses the situation. Others write about it, and through the 1970s and into the ‘80s, that’s what Creem did.

The magazine documented the tension between fan and artist, between expectation and reward, between idolatry and disgust. It was at its best from 1972 through 1976, when its writers were covering a particularly turbulent (and fat and bloated) moment in rock history. With an eye for the absurd but with their hearts open and wounded, Creem managed to capture on paper an era when some sort of mass culture rock ‘n’ roll dream, however full of shit it was, had died—but before a response to it, punk nihilism, had blossomed. Added into the mix: the first generation of so-called rock critics coming into their own.

Much has been written about Creem magazine’s long-form writing in the 1970s, and some of its best pieces have been anthologized. During its glory years, the publication packed in its masthead, among others, Lester Bangs, Robert Christgau, Ben Edmonds, Dave Marsh, Jaan Uheleszki, Greil Marcus, and Ed Ward. Vanity Fair columnist James Wolcott wrote about film and music, and longtime Village Voice writer (and current New Yorker photography critic) Vince Aletti’s “Tighten Up” column covered New York nightlife from an insider’s perspective. Charles Bukowski, Patti Smith, Richard Meltzer and Nick Tosches penned features or columns.

Edited and published in and around Detroit, first in a three-story warehouse, then on a 120-acre farm, then in suburban Birmingham, Michigan, Creem at its peak documented the so-called lost years of rock with a vengeance, analyzing from the industrial Midwest the goings-on in London, New York, Los Angeles, and wherever boogie rock was based.

Absent from the conversation, however, is any mention of the littler, more ephemeral sections in the magazine, those containing perhaps less ambition but just as much attitude. They serve as adjectives in the bigger narrative: fanciful asides, matter-of-fact interjections—personality—which, when recorded by oft-exasperated witnesses, paint the history of the era with rococo flourish.

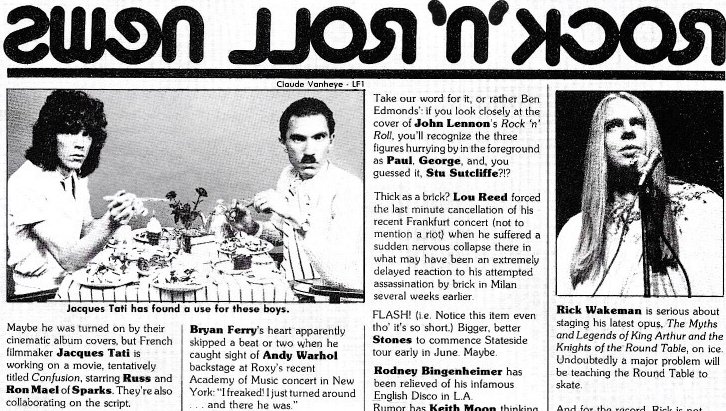

Rock ‘n’ Roll News was a two-page front-of-the-book section which, like Rolling Stone’s long-running Random Notes, reported the comings and goings of rock royalty. It covered band signings and break-ups, label gossip, tour news, injury reports—little crumbs of information scattered across the floor of history. Individually, each is miniscule. But with a little bit of sweeping, you end up with, well, a pile, which is much easier to pick through.

Some of the briefs suggest a near-miss alternate universe. What-if scenarios abound. Take this item from summer 1973: “Bids are getting outrageous for the jam tapes cut at Brian Wilson’s Bel Air home, featuring Wilson, Alice Cooper, Danny Hutton and Iggy Pop. Labels with an inside track: Columbia and ESP.”

Or this one, which nearly explodes my head: “Not long ago, head Kink Ray Davies wrote Vincent Price a fan letter. Price then rang Davies up and said, ‘Raymond, how are you? Do you wanna produce my next album?’ Ray said sure. So if it comes off, the album will be recorded in America, with Vince reading the great bards to musical settings provided by Ray.”

Some are surreal, others tedious and, 35 years later, inconsequential. History hasn’t treated Burton Cummings and the Guess Who kindly, though Creem most certainly did. Johnny Winter was a God. And do we really care that Black Oak Arkansas in 1973 bought their own town, including 1,300 acres deep in the heart of the Ozarks? That they stocked the rivers and fields with deer, wolf, bear, bass and trout?

But moving through the issues 35 years later, the moments start to compress, and something magical happens. Like a time-lapse camera chasing shadows on a street corner, watching history unfold through Rock ‘n’ Roll News reveals a new vision of weird moment in time, when war, Watergate, and Rick Wakeman were in the public eye, when prog rock battled proto-punk, when glam got sparkly, when circuits were shrinking, when rock criticism was constructing a rough-draft narrative and wrestling with the pages.

Sometime in the nineties when I was a buyer at a record store, a pile of Creem magazines, nearly the full-run from 72-76, landed on the counter, and I bought them for twenty bucks. My run begins with the March, 1972 issue, so by necessity—and convenience—this particular history begins there, too.

It was a sloppy time to cover rock culture. First and second generation gods Elvis, the Beatles and Dylan were moseying into middle age, some more gracefully than others. Their replacements arrived bright-eyed and Little-Richard fabulous, androgynous, larger-than-life freaks on a ride. Elton John, Iggy Pop, David Bowie, and Mick Jagger mugged for the cameras and sang their songs, and in their downtime happily doled out stories from their adventures to feed a hungry public.

Alongside them were a bunch of hard-working blue collar dudes riding the rock for a living, the Allman Brothers, Bachman Turner Overdrive, and the J. Geils Band earned their drinking money, and then some, onstage.

The cover of the March 72 issue features a clean-shaven John Lennon under the banner, “Free John and Yoko.” Inside is a review of a December 1971 benefit concert in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for jailed White Panther leader John Sinclair. The Plastic Ono Band appeared last on a bill which also featured performances by, among others, Stevie Wonder and Archie Shepp, along with speeches from Jerry Rubin, Bobby Seale, and Allan Ginsberg.

Creem was disappointed by Lennon’s performance, to say the least, describing the ex-Beatle as “a minstrel wag who looked like he’s just walked out of Vidal Sasson’s (sic) salon and into an Ann Arbor coffee house.” The band played four songs. Reports the magazine: “People walked out on them. It was a rational act. In a word, they were awful. The music was boring. And it was four a.m. Most of us other revolutionaries didn’t have chauffeured Bentleys to drive home in.”

Later in the same issue, Lester Bangs reviews Yoko Ono’s book, Fly, and can’t resist opining on her vocal stylings: “Yoko Ono couldn’t carry a tune in a briefcase.” In the reviews section, Greil Marcus assesses Wild Life, the latest offering from Paul McCartney’s Wings. The review is titled, “Meanwhile, Back in the Suburbs.” Writes Marcus: “Paul and Linda are offering themselves as the petit bourgeois alternative to the millionaire bohemian ethos of John and Yoko.”

Rock ‘n’ Roll News a few months later boils the Beatles news down to its essence, reporting: “The Beatles Fan Club folded officially at the end of March. Announced Ringo: ‘We don’t want to keep the Beatles myth going since we are no longer together.’” But the public was as interested in the untangling of the myth as it was the myth itself, and for the next four years Rock ‘n’ Roll News chased the ex-Beatles, hounded them, lobbed tomatoes at them from Detroit.

In 1973, we follow Paul McCartney to Lagos, Nigeria, where he is recording an album. Writes the News: “He’s reportedly been accused of exploiting African music, and was told by Fela Ransome-Kuti … that it was his ‘Patriotic duty’ to stop foreigners from stealing African culture. The trouble seems to have started when Ransome-Kuti attempted to add congas to a track that McCartney didn’t think needed them.”

Ringo Starr during this period is making records (“Back Off Boogaloo” was #2 on the charts that month), making cameos on David Cassidy records, taking acting classes, and working Hollywood. Writes the News: “Ringo Starr wants Cheech and Chong to be roadies in his new film.”

We follow George Harrison’s charity work for Bangladesh, we stumble through with Lennon as he wrestles with visa problems and the Nixon administration, as his relationship with Yoko hits the skids. “John Lennon rapidly going bald?” asks the News in the summer of 1975. “Well pix may not show it but word has it he’s been frantically shopping around for a scalp specialist with a cure.”

As Lennon’s hair thins, Bob Dylan’s raising babies with Sara and, explains the News, thinking of moving to an Israeli kibbutz. He occasionally lets loose, though, the proof being this item: “And yup, that was Dylan leading Cher, George Harrison, Tony Curtis, Dean Martin, and David Cassidy in a conga line at the big bash about the Queen Mary a couple weeks back.”

Another icon, Elvis Presley, is gaining weight. Creem rides him through the early 1970s with a kind of baffled awe. Vince Aletti in 1972 attends an Elvis press conference in New York City. The King dutifully answered questions, writes Aletti, but “what he seemed to enjoy most was standing up to show off his belt, a monstrous thing made out of several gold plaque-like squares strung together. He said it had been an award of some sort and everyone took pictures.”

Snark.

The darker the night, the brighter the light, it’s true, and twinkling up there in the moonless sky were a few charismatic stars, androgynous frontmen who wore sunglasses that shot sparks, girly-men in gold lamé tuxedos, fire-spitting blood-barfing bassists, spiders from Mars, warlocks with magic wands. Iggy Pop was the king of Creem’s Detroit, even if Alice Cooper was much more famous—and got a ton of ink. (Fellow Michiganer Ted Nugent, on the cusp of superstardom, is described in Creem’s pages differently, as being “renowned as a Nimrod.”)

Bolan and Bowie, Alice Cooper and Rod Stewart, Townsend and Moon, Lou Reed in many shapes and sizes, and always, always, always, of course, Mick and Keef. “‘Probably reliable’ were the words used by Rolling Stones’ spokesman Les Perrin to describe rumors that Mick Jagger and Andy Warhol are teaming for a Broadway musical to star Mick’s popstar wifey Bianca,” reports the News in 1974.

Another that same year: “Hey, look, Keith’s back! That’s the tone of rumors circulating London which have it that Keith Richard, an easy winner in the ‘who’ll be the next popstar to kick off’ speculation derby, has suddenly come back to life and has reasserted himself as the strong arm in the Rolling Stones scheme of things.”

Creem was almost as obsessed with David Bowie’s rising star as it was with the Stones, even if it was slow to acknowledge. Writer and editor Dave Marsh, in a review of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, early on made a dire prediction: “David Bowie may become a star this year, or he may not. This may or may not make a difference in your life. But, for all the people who are assured it will, take it easy: it’s unlikely.”

Marsh, we know now, missed the call on Bowie (though he won big when he bet on Springsteen), and over the next few years the News covered Bowie’s every dalliance—and there were many. Of a spring 1974 European tour, the news reported (rather clumsily) that Bowie “vows to make it the most spectacular rock show ever, with five separate stages he’ll be jumping around, and there will always be something else happening on the four stages he’s not on at that moment.”

Other items describe shelved plans for a stage musical based on George Orwell’s 1984. Another: “For his next studio album, David Bowie is promising an acoustic oriented album of protest songs, to be called either Revenge or maybe The Best Haircut I Ever Had…” In the next issue: “According to gossip ace John J. Miller, Elton John is ready to compose, produce, and star in a rock opera version of Hamlet. His Ophelia? David Bowie, of course.”

Dave Marsh was long gone by then, having left the magazine for New York’s Newsday in 1973. He says that the Rock ‘n’ Roll News section was created while the magazine was still in downtown Detroit, and added into the magazine by the late Creem owner and publisher Barry Kramer, in part to compete with Rolling Stone.

“Barry just thought we ought to do everything,” says Marsh, “in the same way that Rolling Stone could be said to do everything. And he didn't imagine a rock zine without a ‘news’ section, or maybe I mean a gossip section.”

Prior to Marsh’s departure, he wrote the section along with a handful of regulars, including Lester Bangs, Jaan Uhelzski, and Ben Edmonds. Their publishing lead-time was seven weeks out, he says, which made coverage of “breaking” news impossible. “So it became all spin and not much weight, and that's never made me comfortable.”

Jokes Marsh: “We were reading Billboard and rewriting it. But the news was old, so we had to make it funny, put our spin on it.” He adds that although he remembers little about the Rock ‘n’ Roll News section, he recalls that it was easy to come up with tidbits because the music business was relatively small: “Everybody’s talking to everybody within the situation.” Being in Detroit allowed access to the musicians, most of whom hit the Motor City on every tour. “If you’re in Detroit on a day off, who else are you going to talk to? One or two radio stations? And maybe a newspaper guy.”

Nationally, Marsh struggles to recall any real competition for eyes beyond the monolithic voice of the counter culture, Rolling Stone. He says that the underground weeklies were starting to make an impact, as were a few smaller magazines such as Fusion, Rock, and Changes.

Adds Marsh: “Rolling Stone had hegemony, and you could tickle that, you could challenge it, you could subvert it, but by the early 1970s the music industry had pretty much made a decision about who their new flagship was, and it would have taken not only an extraordinarily good magazine, but a real screw up on Jann’s (Wenner) part [to lose it].

Marsh thinks that Creem’s snarky aesthetic (which to my eyes manifested itself fully in the Rock ‘n’ Roll News section) was a reaction to “the sobriety of opinion in all of the publications—including Rolling Stone. They had far too narrow a sense of what was important and how you could express an important idea than we did. I don’t know what the problem was. Maybe they didn’t smoke enough dope. Actually, having been at Rolling Stone later, I know that wasn’t the issue.”

As Creem grew popular, says Marsh, it became more frivolous, which is one reason why he quit in 1973. He explains: “It went from being super serious some of the time, and super silly the other time, and in the middle the rest of the time, to being silly all the time, pretty much, to being the cartoon of the rock fan.”

But it’s that frivolity in the few years after Marsh left which makes those little News sections so illuminating. Whether Creem was betting on Bowie to sell its magazines, or Elton John or Slade—whom they pushed particularly hard—it kept track of its chosen heroes. Flip from month to month and follow Sly Stone’s drug busts, witness Jethro Tull flute-solo its way to fame, rejoice at Peter Gabriel drifting on wires across stage as an astonished Phil Collins looks on; watch in stunned silence as Keith Emerson performs solos on castles made of Moogs.

Thirty-five years later, we know how many records Rod Stewart sold, we know to cringe when Sly gets busted, because it’s a portent. The bio-pics have played themselves out in real time, and what was once a chuckle—“Phil Spector was held up on Sunset Strip. The bandits made off with $2,800 spectorbucks, and if you think he was twitchy before …”—has morphed into a clue nestled in the afterthought pages of a dead magazine. Do a Frankenstein on it and what zaps to life is subtext, context, and the pretext for punk rock.

Plus, who wants to tackle hegemony when you’ve got Keith Moon’s self-destruction to report? The Who drummer roars through Creem’s news section, a Tasmanian Devil with a dozen lives to burn. He buys Rolls Royces like they’re candy, and the News reports each purchase. October 1972’s section reports that “Keith Moon was hospitalized in July …with an abscess incurred while doing a double somersault while touring with Sha Na Na in Belgium.”

April 1973: “Keith Moon’s in another kind of jam: he was fined $35 for not having a license for his 12-gauage shotgun. Said Moon to the court, ‘Do you take American Express cards? I haven’t used money for some years.’” A few months later we learn that “Keith Moon, death defying drummer for the Who, was wounded in action again. A ‘magic wand’ gimmick he was experimenting with for the Who’s new stage act exploded unexpectedly, releasing a pellet which grazed his stomach. He was rushed to a local hospital, and released after treatment.” Early in 1974 Moon is “banned from the BBC TV bar, for apparently pinging a barman’s braces, whatever that means.”

As rock got fatter and fatter—as Pink Floyd toyed with working with Rudolph Nureyev, as the News reported that the Allman Brothers and the Grateful Dead were planning a series of concerts reportedly to last somewhere between eight and twelve hours—some bits take on an accusatory tone, like the testimony of a prosecutor arguing for the death penalty. The divide between the drugged-out superstar glamour and the three-chord chunka-chunk of proto punk was bigger than Madison Square Garden, and held a bunch of bored and bonged-out fans ready to rock.

And so when they read in Rock ‘n’ Roll News about that real estate developer who got into a tussle with Elvis’ bodyguards? “They not only refused him entry, but started stomping his ass…” and Elvis not only didn’t come to the rescue but did some stomping of his own? The fucking nerve. The fucking nerve. If this is the way they’re going to play it, we’ll hit back. Ergo: Rock ‘n’ Roll News.

You punch your idol, a knuckle-buster to the nose: “Last time Mick and Bianca were in New York, Manhattan’s leading friend of the great took Mick by Miles [Davis’] house to introduce them. Miles was typically frank about how he felt about ‘white-ass’ musicians, and Jagger and Friend left, without their audience.”

And then a body blow: “Following a recent Sly & the Family Stone gig, Mick Jagger was refused a backstage audience with Sly, told that Sly ‘did not wish to see him.’ Something to do with the fact that Mick had been ‘too busy’ to see Sly when the two were in LA some time before that.”

You don’t see that very often: Mick Jagger denied. There is justice. Our heroes are human.

This essay was originally published in Stylus. A slightly different version was presented at the 2007 EMP Pop Conference in Seattle.